This is @edpsychprof's weekly newsletter for those interested in transforming schools to become places where children (and adults) can thrive.

Part 4 of a five-part series on principles that I believe are essential to creating a school culture that helps children thrive. I developed these principles to serve as the foundation for the charter school I founded, yet the principles are universal, based in robust theory and research from psychology and education. Today, we discuss the No Child Left Bored Principle, in which students are given regular opportunities to engage in authentic, interdisciplinary learning based on their interests.

Student engagement in learning is the pivotal factor in student success. When students are bored by school and disengaged from what is being taught, they are not learning. It is so important to build on students’ existing knowledge and engage their curiosity when planning a lesson. This principle, a twist on the controversial No Child Left Behind federal regulations a few years back, highlights how important student engagement is to learning. Engagement can happen in a variety of ways, from building on students’ interests, to engaging them in authentic problem solving, to tapping into their existing talents, skills, and knowledge. Learning is not boring! That schools have made it so is my 2nd ranked complaint about them (the first being the lack of equity).

To illustrate, I want to tell you about my Dad, who passed away in 2019 but remains with me, shaping how I see schools and their purpose. I wonder what kind of life he would have had if schools had tapped into his interests, built on his strengths, and engaged him in authentic problem-solving? The schools of his time did nothing like this. Instead, the teachers droned on and on, and he would get reprimanded for staring out the window, waiting for the school day to end.

But he wanted to learn! He told me once that he would sit in school wondering what the purpose of a particular lesson was. “Michele, you know I like chess. You can’t play chess until you know the objective. The goal is to checkmate the king. I get that. I need to know that to play the game well. I was never taught why what I was learning was important—what was it useful for? If the teachers had started with that, I think I would have paid more attention.”

Instead, my dad wrote poetry and daydreamed about inventions he would make, and at 17, he joined the Navy. There, his eagerness to learn was rewarded as he studied to become an electrician. He was fascinated with Ohm’s Law, so much so that many years later, he sat me down to teach it to me one afternoon when I was a child. I still remember the careful pencil marks on the yellowed graph paper. How reverently he spoke about the relation between current, voltage, and resistance, which made electronic devices possible. “Remember this,” he told me. “Isn’t it amazing?”

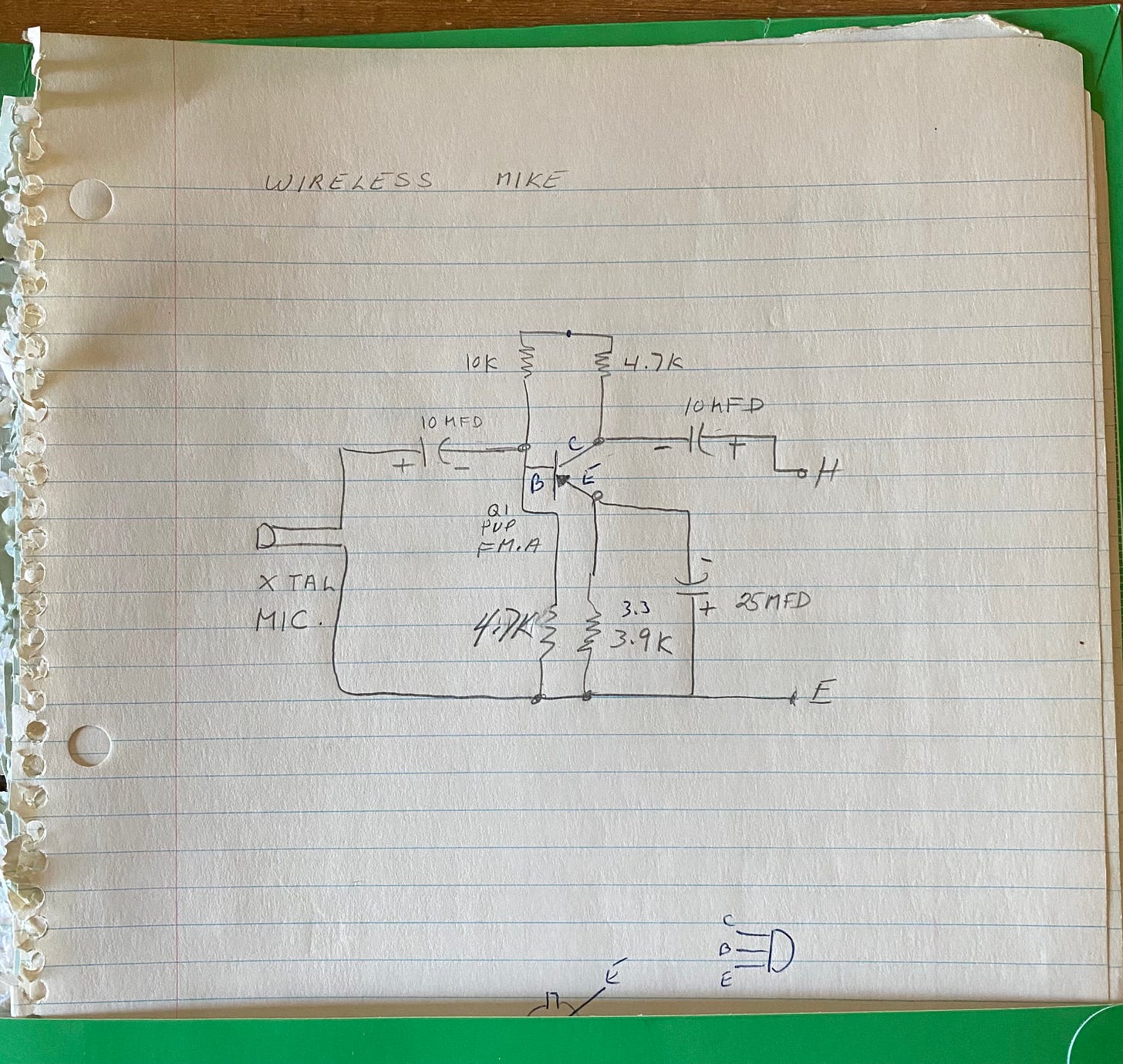

After the Navy, my father became a ballroom dance instructor in the Catskills (kind of like Patrick Swayze in Dirty Dancing, but less dirty and more dancing). Realizing he wanted to be able to support a family someday, he left dancing to become a telephone repairman in New York City, studying the telephone industry and management until many years later he, an uneducated kid from the Bronx, became regional VP of a national telecommunications company. Though he was good at his job, he never felt fulfilled at his work. Going through his journals after his passing, I found page upon page of inventions that never came to fruition. One of them was for a wireless microphone, another for a device to spike a lawn for fertilizing it, and another for an automatic door. These were written from 1969-1971, well before such inventions existed. His lack of confidence in himself as an educated person stopped him from pursuing these ideas.

My father’s love of learning blossomed in retirement where he took up woodworking, painting, and building beautiful things. My father was lucky—back in the 70s you could work your way up to management without a college degree. Nowadays, most entry level professional jobs require a four year degree. What about kids today? Though there are many opportunities to learn on the internet, a lot of kids still need guidance and support, feedback and encouragement. Public schools can provide that, but only if they engage students first.

Me and Popi, circa 2001

I would love to hear your thoughts--they help clarify my own thinking and contribute to the larger discussion on this topic. Plus, your responses help create community around this idea of school transformation. Who knows what good we can do together?

Get this newsletter delivered fresh (and free) to your inbox by subscribing below: